Rummaging through the worn backpack, Strass pulled out and counted each potion of mind-shielding—three remained. Sharing a knowing glance with his friends, Strass passed out the potions: first to Kara, next Azreal, and then he motioned for Val to take one, but the rogue waved it away. Quaffing their remaining potions, the heroes prepared to enter the dark cave that stood before them. Strass ignored the feeling of dread that ran down his back.

Rummaging through the worn backpack, Strass pulled out and counted each potion of mind-shielding—three remained. Sharing a knowing glance with his friends, Strass passed out the potions: first to Kara, next Azreal, and then he motioned for Val to take one, but the rogue waved it away. Quaffing their remaining potions, the heroes prepared to enter the dark cave that stood before them. Strass ignored the feeling of dread that ran down his back.

Welcome to the table. During a particularly dire battle, one of the player characters died. It was a somber moment at the table and prompted some conversation about death. Today, let’s talk about death and how it can be handled in your game.

What is player character death and how can it appear at the table?

Sprinting down the darkening tunnel, Strass could hear the eerie shuffling of the cloaks behind him. Where was Val? Did his potion wear off? Strass could hear Azreal and Kara catch up to him, their faces cast by shadow. Gesturing to the nearby rock outcroppings, Strass whispered, “Get cover. We’ll ambush them when they come this way.” A minute later, Strass saw Val haggardly running to their hiding place.

Character death seems pretty straightforward. Something goes awry, the dice don’t go the player’s way, and the character dies. Yet there is a nuance to the way characters might bite the dust. In the article, “Death Sucks” (linked here), the Angry GM describes death by breaking it into three classes:

Character death seems pretty straightforward. Something goes awry, the dice don’t go the player’s way, and the character dies. Yet there is a nuance to the way characters might bite the dust. In the article, “Death Sucks” (linked here), the Angry GM describes death by breaking it into three classes:

- Class 3 deaths are those deaths where players had little choice in their death, and these often can be blamed on the GM (e.g. “a trap activates, you’re dead”).

- Class 2 deaths are reasonably fair deaths; you die fighting a monster, the dice are unlucky.

- Class 1 deaths are where players buy into the death, knowing that their decisions or actions are risky, and they’ve made peace with the possibility of death.

Considering death in nuanced ways reveals how death can be handled and what preparations should be made prior to character death. Caught in a deadly fight, Val’s death fell in the range of class 2.

Death almost always slows down the game. Players try to change their actions, wonder about the character’s fate, and sometimes, disconnect from the game altogether. For both players and GMs, death needs to be carefully considered. If you are the GM, consider how death plays a role at the table. Often, deaths can help create change in the other characters or prompt a new mission for the characters to go on. If you are a player, consider any plans you’ve made for death. If your character is dead, how will you still participate in the game, even if this means just watching, while your friends fight for survival or seek a way to bring you back?

What can both GMs and players do to prepare for death?

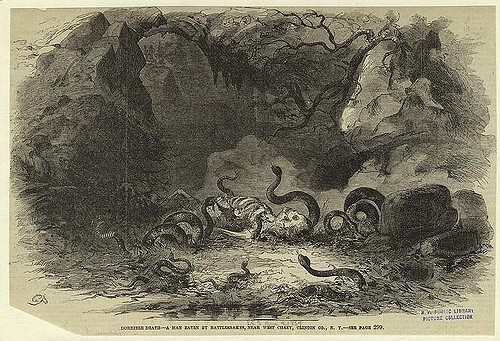

Shouting in rage, Strass tried to break through the wall of combatants between him and Val. The rogue had stumbled just before passing their ambush point and was now surrounded. The creatures fought ferociously, and Strass knew that he couldn’t save Val. In the dim light, Strass watched as one creature stooped over the still form of Val. The sickening crunch that echoed in the dark caves a moment later filled Strass with fear and rage. Redoubling his onslaught, Strass called out vainly to Val.

Whether you are a GM just starting out or a veteran GM, I recommend talking to your players about death before it happens. In my games, some of my questions are:

Whether you are a GM just starting out or a veteran GM, I recommend talking to your players about death before it happens. In my games, some of my questions are:

- Do you want your character to be resurrected?

- Has your character written a will?

- Would you like to play a new character even if resurrection was possible?

By asking questions like this, either before the game or before a particularly dangerous session, both you and your players can prepare for death, reducing the surprise and potential problems that arise when a character dies. These questions do not need to be posed only by the GM; players may also consider these questions and many others well before a death occurs. For games that are focused on roleplaying, these questions can be converted into in-game questions, posed by NPCs or the players, often resulting in rewarding, character-building experiences.

How can death be beneficial?

Strass’ axe slammed into the side of another abomination. Just ahead of him, the unmoving form of Val lay underneath the foot of one well-armored. Strass glared at it, raising his axe in challenge. Val’s murderer raised their own sword in response, and a voice entered Strass’s mind, “The last thing your friend thought was, ‘I’m sorry Tyrash.'”

When Val died, I asked Val what his final words would be: Val’s final words were an apology to Tyrash, a character who died in an earlier session. It was a great roleplaying moment and added greater significance to Val’s death. Creating space for a character’s final words helps players have one last moment of importance before dying and helps everyone at the table have closure over the loss of an ally.

When Val died, I asked Val what his final words would be: Val’s final words were an apology to Tyrash, a character who died in an earlier session. It was a great roleplaying moment and added greater significance to Val’s death. Creating space for a character’s final words helps players have one last moment of importance before dying and helps everyone at the table have closure over the loss of an ally.

Careful planning and preparation can make any death, even those that surprise you, run smoothly. The turn of fate may even be embraced by the players. If players have a chance to consider death before it happens, class 1 and class 2 deaths become more frequent and may become valuable moments of roleplaying. Class 3 deaths, as noted above, often create less space for opportunities of roleplaying and require much more attention to the pace and atmosphere of the table. Since class 3 deaths can be attributed to GM mistakes, these kinds of deaths likely require pauses at the table, apologies inside or outside the game, and flexibility on the part of both player and GM. I will cover these types of deaths in a later article.

Bloodied and weak, Strass knelt over Val’s body. All around him lay defeated or killed opponents. As Strass looked down at Val, he couldn’t help but feel regret. If he were faster or stronger, could he have saved Val? Should he have taken that last potion? Azreal’s hand comfortingly fell on Strass’ shoulders. “Take him with us. We’ve got to get out of here.”

Let’s sum up,

- Preparing for deaths at the table can help keep the game moving and make dying something that although sad can be still enjoyable for both the dying player and the others at the table.

- Try not to rush a character’s death. Allow time for a final word or a moment of closure. Doing this helps emphasize the death, respecting both the player and the fallen character. It also gives the rest of the table opportunities for roleplaying.

- Prepare, prepare, prepare. Surprise deaths happen, and when they do, both players and GMs should have a sense of what to do. Setting expectations helps the game run smoothly when the worst happens. For players, start thinking early about what happens if your character dies and make plans about what you would want to have happen.

In the comments below, share your best character death experience. What made it so good and what would you have changed?

See you at the table!

Comments are closed.