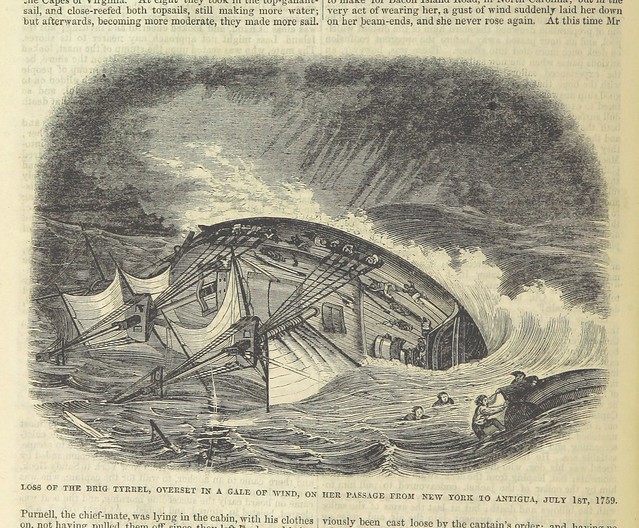

Kara’s chest flared painfully with each breath. Next to her, Strass’s left arm hung uselessly at his side. Thick, muscular tentacles lay around them, writhing as if still controlled by their monstrous master. A few dozen feet before them, the kraken lay defeated, its great yellow eyes unmoving. Nearby, Azreal tended to the large gash running across Val’s chest. A whirlpool surged suddenly at the center of the strange ship graveyard, sucking everything into it. In an instant, the heroes were drawn into a black abyss.

Kara’s chest flared painfully with each breath. Next to her, Strass’s left arm hung uselessly at his side. Thick, muscular tentacles lay around them, writhing as if still controlled by their monstrous master. A few dozen feet before them, the kraken lay defeated, its great yellow eyes unmoving. Nearby, Azreal tended to the large gash running across Val’s chest. A whirlpool surged suddenly at the center of the strange ship graveyard, sucking everything into it. In an instant, the heroes were drawn into a black abyss.

Welcome to the table! This session marked the end of a campaign arc. The players had entered a new region, matched wits with a villainous uncle, and fought with horrific creatures of the abyss. Amid all of the adventures, one moment stood out during the final fight: the players were deeply unsettled because the monstrous aboleth was trying to be killed. Today, let’s talk about manipulating expectations.

Cliché & Expectation

In fantasy and science fiction, there are things that always seem to come up—Dragons, spaceships, a world-ending artifact, and villains hellbent on destruction make a short list of the clichés often found in these genres. In RPGs, players expect magical or unique items, fantastic worlds, and powerful foes. It is this last expectation that a GM can manipulate to really make players worry. When players come to expect horrifying, dangerous monsters, introducing monsters that are the opposite causes a break in that expectation and forces the players to question whether something else is happening.

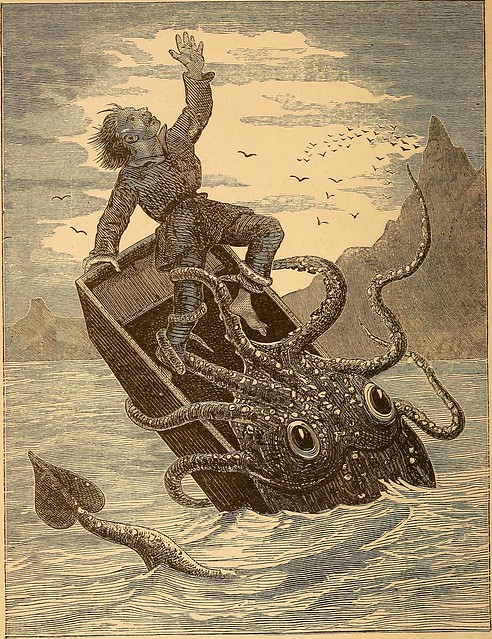

“You’ve fought well… but all things come to an end. Give yourself over to Ruin.” The voice painfully filled Kara’s mind. Snapping her eyes open, Kara saw her friends close by, holding their heads and looking dazedly around. Turning her attention to the thing floating in front of her, Kara took in the hideous form of the aboleth. Tentacles twisted in on themselves, concealing a slime-covered body. Three blood-red eyes stared at her through the wriggling mass. Roaring in fear and anger, Kara raised her staff, hearing her allies do the same, and she struck the aboleth. “Yes! Come! Do your worst…” the voice called to her.

“You’ve fought well… but all things come to an end. Give yourself over to Ruin.” The voice painfully filled Kara’s mind. Snapping her eyes open, Kara saw her friends close by, holding their heads and looking dazedly around. Turning her attention to the thing floating in front of her, Kara took in the hideous form of the aboleth. Tentacles twisted in on themselves, concealing a slime-covered body. Three blood-red eyes stared at her through the wriggling mass. Roaring in fear and anger, Kara raised her staff, hearing her allies do the same, and she struck the aboleth. “Yes! Come! Do your worst…” the voice called to her.

A Strong Final Foe

In our session, the characters had been working up to a final foe, an aboleth named Ruin. Over the course of the arc, the characters fought against hordes of aberrations and deadly beasts, nearly dying a number of times. When the final fight finally came, the characters were anxious to see what would happen and prepared for a wild battle. I tried not to disappoint, and after fighting both a kraken and the aboleth in a ship graveyard, the players managed to drive Ruin back into its lair—its former prison.

Often players assume that a final fight needs to be hard, dynamic, and full of epic moments. While these traits are important, when they are manipulated or when you provide the opposite, you force players to start looking for what is wrong. When the characters started fighting Ruin, they found the fight to be eerily easy. Ruin did little to stop the characters, and every time that the characters attacked, I emphasized that Ruin “leaned into the hit.” During Ruin’s turns, it would only attack once, never focusing on one target. In this moment, I watched the faces of the players grow worried. The focus of the fight started to shift, the players realizing, without me explicitly telling them, that there was something more happening at the table. One of the players even raised the question of whether Ruin wanted to die for some evil ritual. To make matters worse, at the start of the round, the players needed to successfully avoid a life-draining effect that would lower player’s hp by half, thus ensuring that the players would fail if the encounter was drawn out.

Azreal watched as the aboleth leaned into his attack, his sword cutting deep into the creature’s flesh. Years of fighting told him that something was wrong, that this should be harder. All the while, the voice in his head grew more excited, “Cut, slash, and hack. Yes… soon there will be nothing left of me here.” Lowering his blade, Azreal looked around the room, taking in a large viscous pool and massive rune-covered hooks that hung from chains secured to the pool’s edge.

Giving Hints

Manipulating expectations can have mixed results. Over the years, I’ve watched players grow excited, confused, even angry when things don’t go the way they thought it should. When I was designing this encounter, I was careful to leave clues—shown in the environment, the monster’s actions, and my narration—to clue the players into other options available to them. As the players attacked Ruin, they grew more and more worried that they were doing something wrong. I intentionally started drawing the player’s attention to the hooks and chains that hung in the room, hoping that they would pick them up and use them to attack Ruin.

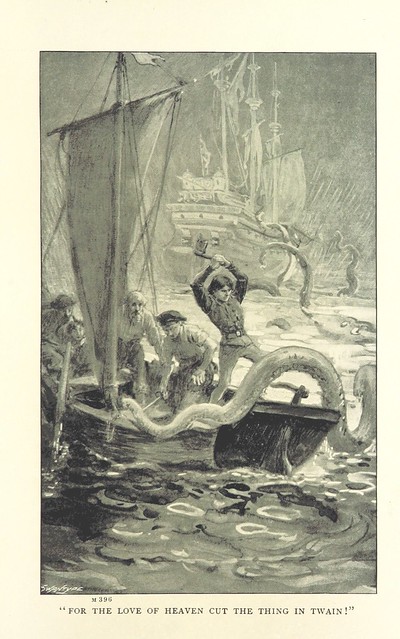

Cluing the players into available options should be a common practice for GMs, but it is particularly important when challenging players’ expectations. By indicating to the players that the hooks in the room were “old, tangled with portions of dried flesh, and covered in arcane runes”, the players could intuit that these could and would be helpful in fighting the aboleth. Eventually, Azreal decided to use one of the hooks as a weapon and discovered that they were both magical and built to harm Ruin.

Azreal took one of the hooks in his hands. It was impossibly light for its size. The runes that covered the hooks flared to life. Visions of a divine being, mighty and beautiful, filled Azreal’s mind. He knew this god—Pelor, lord of the sun—his patron and protector. The visions showed Pelor swinging the hook, piercing the aboleth’s flesh. As soon as the visions started, they stopped, and Azreal smiled, raising the hook above his head.

Patterns, Patterns, Patterns

Patterns, stereotypes, and clichés provide both familiarity and predictability to the game. Players come to rely on certain patterns because they are effective. Breaking those patterns with careful planning can result in players growing uncomfortable, which in turn can lead to amazing moments of inspiration at the table. During this session, the players were vocally and physically uncomfortable when the final villain was doing nothing to stop them. When the players finally picked up the hooks and the villain flinched with fear, the looks of excitement and accomplishment that radiated from the players was worth the work.

Patterns, stereotypes, and clichés provide both familiarity and predictability to the game. Players come to rely on certain patterns because they are effective. Breaking those patterns with careful planning can result in players growing uncomfortable, which in turn can lead to amazing moments of inspiration at the table. During this session, the players were vocally and physically uncomfortable when the final villain was doing nothing to stop them. When the players finally picked up the hooks and the villain flinched with fear, the looks of excitement and accomplishment that radiated from the players was worth the work.

The first hook sank easily into the aboleth, and the voice inside Azreal’s head took on a panicked tone. The lethargic aboleth suddenly swelled with power, lunging out at everything around it. Azreal shouted to his friends to grab the other hooks and prayed, hoping that his god would bless the other hooks as he had done to the first one.

Let’s Sum Up

- Noting the patterns your players fall into and the expectations they have can pay off in the long run. Keep a few notes about these patterns to remind you where you could change the game when needed.

- Breaking expectations can yield amazing moments at the table but should be done carefully. Without support and proper clues, the players may flounder and grow angry or frustrated.

- Not every final villain needs to be powerful, but the encounters they are in should be dynamic and fun. You can accomplish this by weaving social and environmental encounters into a combat situation.

See you at the table!

“Strass’s left arm hung uselessly at his side.” Fiction that isn’t supported by the rules isn’t helpful to your argument. (Perhaps you were playing RQ?)

Assuming 5th edition D&D, page 272 of the DM’s guide lists the optional rule of Lingering Injuries, one of which can be the loss of an arm. In addition, page 54 of Xanathar’s Lost Notes to Everything Else expands upon these options with a d100 table of injury options, notably the breaking of an arm causing it to be useless.

Thank you. That’s very helpful.

Loved it. This is a strong, well-written article. It inspires, it informs, and it’s a damn fine read.

Well done ‘J’.