Welcome to the table. Tonight, my players split up across the town, and unfortunately, each wound up involved in deadly assassination plots. For a GM, a session like this may sound like a nightmare—multiple simultaneous fights across a split party. Yet as the night developed, I discovered an effective way to get the players to tell the outcome of their conflicts. Today, we talk about Narrative Authority and its effect at the table.

Welcome to the table. Tonight, my players split up across the town, and unfortunately, each wound up involved in deadly assassination plots. For a GM, a session like this may sound like a nightmare—multiple simultaneous fights across a split party. Yet as the night developed, I discovered an effective way to get the players to tell the outcome of their conflicts. Today, we talk about Narrative Authority and its effect at the table.

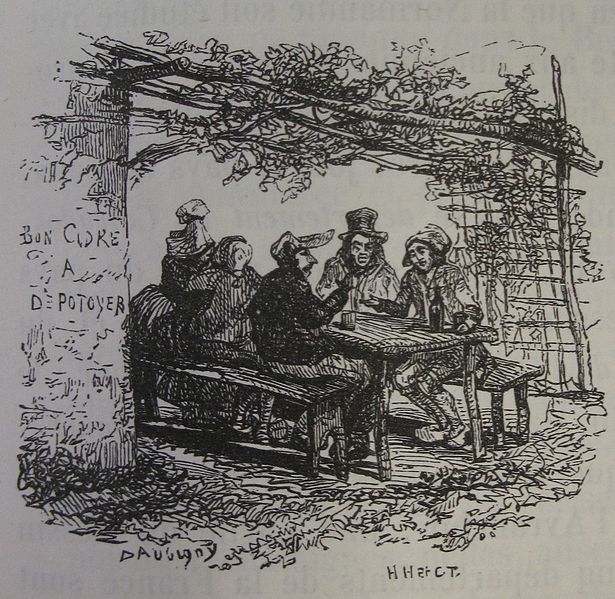

Val and Azreal had been enjoying a perfectly good glass of wine among the nobility of the city when the assassins showed up. While Val quickly vanished into the crowd, Azreal set down his glass and drew his sword, sparing a thought for how the night could have went—dancing, gossiping, flirting. But no, when assassins show up, it’s a night of work, sweat, and pain. Azreal charged from the table to slay the would-be killers.

What is Narrative Authority and how does it influence the table? How can GMs and players manipulate Narrative Authority to enhance the game? When is Narrative Authority detrimental?

Tyrash didn’t expect that his errands would result in being pinned against the wall with a dagger against his throat. The dark-clad assassin’s eyes darted toward the sound of the bustling thoroughfare. That distraction was all that Tyrash needed: his fist caught the side of the assassin’s head.

Tyrash didn’t expect that his errands would result in being pinned against the wall with a dagger against his throat. The dark-clad assassin’s eyes darted toward the sound of the bustling thoroughfare. That distraction was all that Tyrash needed: his fist caught the side of the assassin’s head.

Within the tabletop gaming genre, Narrative Authority describes the “believability” or “reality” of actions or decisions made at the table. In many tabletop games, actions only become real when declared in front of a GM and the GM agrees with those actions. Imagine for a moment that one of the players tells the table that they have a secret item that no one else knew about. If the GM is present, everyone at the table may wait to learn whether the GM accepts that statement. If the GM were not present, many players may ask, “Does the GM know about this?”

Strass drained his twelfth tankard, the harsh ale burning his throat and chest as it settled into his stomach. Stumbling between the small crowd of this night’s drinking companions, Strass pushed open the tavern doors, taking in a deep breath of fresh air. In an instant, his instincts told him that he was not alone. Looking around, Strass made out six figures, seeming to appear from the darkness, the flash of daggers in their hands.

During this session, my players found themselves in fights across the city. Usually, such a situation may result in difficult, slow management of multiple combat encounters. Yet I found an opportunity to place the narrative in their hands. Drawing focus to the battle involving Val and Azreal, I asked the other players to roll four d20s. I informed Tyrash and Strass that at the end of each combat round, they would describe how their encounter was going, using the rolls as a guide, emphasizing that anything they said would be true.

In doing this, I reduced the level of narrative authority held by the GM. By asking Tyrash and Strass to tell how their fights go, I saved the table time trying to run each fight individually and provided opportunities for Tyrash and Strass to completely control their own encounters. In requiring these players to use their rolls as a guide, the players could see how their fight went, giving them time to plan and embellish their stories before sharing with the table. At the end of each combat round, the entire table—including me—turned to Tyrash and Strass to learn what was happening.

[Tyrash rolled a 13] Tyrash’s fist connected with the assassin, but as the assailant stumbled, his blade sliced across Tyrash’s chest, cutting deeply to the bone. Gasping in pain, Tyrash seized the opportunity to jump on top of the killer.

[Strass rolled a 17] Strass smiled, spreading his arms in an inviting gesture. A second later, three of the figures rushed forward and plunged their daggers into Strass’s chest. Strass laughed as barbarian rage filled his eyes. His hands drew forth one of the three daggers and rammed it into the nearest assassin.

Usually, when players take control of the storytelling, they are met with disbelief, requiring a GM to confirm that their actions did take place. Taking moments to explicitly manipulate who has authority at the table can result in your players having more fun in revealing character traits and more immersion across the table. For my players, the opportunity to tell their own combat stories resulted in a surprising show of character development and risk.

Over the course of the fight, Val and Azreal defeated their foe handily. Strass, in beautiful barbaric fashion, decimated the six assassins that tried to kill him, and his story was extremely comical and exciting. But Tyrash’s encounter was much more surprising. Having rolled his four dice and seeing 13, 9, 20, 1, the party was given a narrative that left us on the edges of our seats, increasing the excitement for each round to finish so that we could listen to Tyrash’s encounter.

Tyrash lungs burned for air. After receiving a few deep cuts from the assassin and giving a few blows in return, Tyrash had managed to flee the alley, slide between the wheels of a moving cart, and rush down another alley. A second later, he heard the sounds of a ruffling cloak and spun, too slowly, to see the assassin who was materializing from the shadows behind him. The assassin raised a club and brought it down on Tyrash’s head. All went dark.

Tyrash lungs burned for air. After receiving a few deep cuts from the assassin and giving a few blows in return, Tyrash had managed to flee the alley, slide between the wheels of a moving cart, and rush down another alley. A second later, he heard the sounds of a ruffling cloak and spun, too slowly, to see the assassin who was materializing from the shadows behind him. The assassin raised a club and brought it down on Tyrash’s head. All went dark.

The entire table sat in stunned surprise as the narrative came to an end. I, for my part, quickly began writing down what the party would need to do in order to save their friend and many of the players demanded to know if Tyrash was dead or not. By giving Tyrash’s player narrative control, they developed a plot line that I was not prepared for and that excited everyone.

Consider this as an infrequent tool to handle separated parties or to emphasize profound moments for players to roleplay. By relinquishing Narrative Authority, the table becomes a greater space for collaborative story telling. But don’t overdo it without talking with your players. After implementing this combat option into your game, I recommend asking your players if they thought it was fun.

Let’s sum up:

- Narrative Authority is something GMs and players should be aware of as they run their games, for manipulating it affords interesting, exciting moments at the table.

- Granting your players opportunities to describe their own encounters can result in surprising character development or player choices.

- These opportunities are simple and powerful and help enhance your game or manage the table.

See you at the table.