Sean Macdonald never intended to become a freelance RPG cartographer. An internet programmer by trade, he got into RPG cartography through his work as a website designer. He started his freelance cartography career in 2003 mapping the Dragonlance Campaign Setting.

Three years later he won a gold ENnie for Tasslehoff’s Map Pouch: War of the Lance. His 2007 contribution to the Pirate’s Guide to Freeport (Green Ronin) won the ENnie for Best Cartography.

Michelle Nephew, Tenured Editor at Atlas Games, praises Macdonald’s “professionalism and attention to detail.” His maps for Tales of Mythic Europe adventure collection for Ars Magica, Nephew said, “Really give a sense of immediacy to the adventure as a whole.”

The immediacy that Nephew mentions is as much a Macdonald trademark as the professionalism. As a result of this combination, Macdonald has worked with every major RPG publisher, as well as small but fierce outfits such as Open Design.

“Sean is a mean and angry man who beats his maps mercilessly,” said Jon Schindehette, senior art director for Dungeons & Dragons at Wizards of the Coast. “Ah, I mean, Sean is one of a small stable of cartographers that I count as a ‘go-to guy’. He is great about hitting deadlines, and dealing will the countless tiny details that RPG cartography calls for. I like the fact that I always know exactly what I’m going to get from Sean, and that the only surprises I ever have to deal with are ‘happy surprises.'”

Around here, we know Macdonald for his beautiful maps, such as those for the Zobeck Gazeteer, KQ#8, Tales of Zobeck, and Halls of the Mountain King.

Jones: How’d you get started making maps? Where’d you learn to do it?

Macdonald: I never set out to be a cartographer. I actually learned the skills I used for making my first maps because I had been hired as a website designer. So I had all the necessary software and learned through trial and error to create different graphics and styles. I was also heavily involved in D&D and the Dragonlance setting in particular. I created a website dedicated to a halfling-like race known as kender called the Kencyclopedia. So I spent most of my time working on that site and developing skills that I would later use in my cartography work.

When Sovereign Press got the license to develop Dragonlance materials for 3rd Edition I was fortunate enough to be a part of that and worked as part of the Whitestone Council of the Dragonlance Nexus.

When a couple of the Dragonlance books were nominated for ENnies I headed to GenCon to attend the ENnies Award ceremony. During that ceremony I was impressed with the different work going on in the industry, but when I saw the work done in the Cartography category I was blown away. The maps were beautiful and functional, not only that, when I viewed them I knew how they had been created. I recognized some of the techniques and skills used and I wondered if I could do something similar.

So when I returned from GenCon I created my first map of the city of Flotsam in the Dragonlance setting and I showed it to Jamie Chambers and he was impressed. So he began hiring me to do maps for the Dragonlance setting. From there I just continued to build a portfolio. I effectively had become a cartographer because I just happened to have the right skills, played D&D and knew the right bunch of people.

Jones: What should a map do? Or, put differently, what is the difference between a great map and “just” a map?

Macdonald: Personally I think a map should tell as much of the story it is representing as possible. So a person can look at a map and tell what is happening within that environment without needing a full body of text to go with it. It’s not always possible. Sometimes the real substance of the adventure is in the text, but if a DM can look at a map and see clues to what is going on in each area of a map, I think it helps them immensely during their games to prevent them from going back and forth from map to text.

A good amount of visual details also gives them an idea of how to represent and area during their game. So whether it be with a mat and ink pens or tiles, if the text says there is a table, a suit of armor and a chest in the room they can take one look at the map and know where those things are. If it’s just an empty room on the map it can sometimes make it difficult to know what the designer had in mind when they created the encounter for that designated area. Should the magical armor that is about to attack be next to the door or across the room? Is the trapped chest in dead center or tucked away in a corner?

I think the most important thing a map can do is make the DM’s job easier at the table and at the same time be something you enjoy looking at and exploring.

Jones: What does a map do for you? What do you like best about map-making?

Macdonald: I enjoy the process of transformation. Most of the time I am working from an author’s sketch and often times those sketches are a decent, very basic representation of what is needed, but they are far from something that could be published. (Although I have to admit there were a few times when I got a map sketch from an author and thought it was nearly good enough, heh.) But taking the initial sketch and researching the text that goes with it and building a new map from those foundations are exciting to me. It’s just a good feeling to finish up a map and take a look at what I’ve created and compare that to what was sent to me.

Jones: What type of map interests you the most?

Macdonald: Maps that are not so dependent on exact measurements. I know it may sound odd since maps usually have to have some sort of scale and a need for accuracy, but occasionally I get to do maps that can be a bit more artistic. It’s just interesting for me to explore different ideas of how to represent something or to be able to illustrate something in a hand drawn manner that would be less about a professional exact map and more creative in nature.

Here is a map I did for Wizards of the Coast that was a little more free form than some maps. It is the ruins of a tiefling city. I wasn’t given a sketch for it, so I worked from the text.

A map nearly always begins with an art director sending me an author’s sketch and some descriptive text, and when possible, the actual adventure text. Sometimes it is just the text and I’m responsible for creating the initial sketch and getting it approved by the art director.

Once I’ve read through everything I will sometimes modify the sketch digitally for a number of reasons. For example, it’s common for me to create a grid (if the map needs one for five foot squares) and align the sketch to the grid. Often times this means re-drawing walls or other symbols to line up. Sometimes I’ll have to add in rough sketch symbols of things that were in the text, but not actually sketched out.

Once I’m happy with the digital sketch I lay it out according to the size of the map requested and print it out.

I take the printed sketch and usually overlay it with a second sheet of paper and draw anything in the map that needs an illustrated look such as natural symbols like trees or rocks or rough stone edges if the map is a location underground. Sometimes I may draw buildings or icons that I don’t already have, such as views of a specific statue from the top down.

When the illustration is completed, I scan the image and overlay the digital sketch. Then I begin the coloring process. I always review any descriptions given to me and look for mentions of specific colors or textures. Is the ground rough; is it grassy or smooth like glass? Is water clean or brackish or even poisoned? Is this a lived in area? If so I’ll need to add some dirt to show it’s an area that is travelled through frequently. All of the descriptive text that I get is factored into how various locations in the map are designed to look. This includes adding in any common icons, like beds, or barrels and things of that nature. Overland maps may have different icons based on the descriptions of the cities or villages.

Finally, when the coloring process is complete I add in any text labels, compass rose and my signature. Then I create a smaller preview image from the final print and notify the art director that it’s ready for review.

Jones: So there’s not much collaboration?

Macdonald: Hopefully, by the time the map sketch is forwarded on to me any collaboration has already taken place.

Once I’ve sent a map off to an art director it is reviewed by the author and any line developers or editors and what I get back is generally a small laundry list of tweaks and changes.

However, I have seen collaboration in action when I worked on the Open Design project Blood of the Gorgon. Specifically, there was a mansion that was sketched out that I created the map for and the map preview went up for the patrons to review and I think it came back to me two or three times for changes before it was completed. And I have to say in that case it really did produce a final map that was more useful and made more sense than the original, because it was not just being looked at from the view of, “what is needed for this adventure?”

For example, a patron asked how a servant gets from the kitchen to the great hall or the master’s quarters, without traipsing through the library or armory first. That made a big difference; I added in back halls and servants’ quarters and all sorts of details that would have been missed if there was no collaboration going on at all. Here’s the map of Armand’s Apartment:

Jones: How has your understanding of map-making changed over the years?

Macdonald: Wow… Looking back at some of the original maps I did four or five years ago compared to today is a world of difference, in my eyes. I have so many techniques that I use now that I just didn’t have the skill set for back then. I have also created a library of my own map icons that I can use that really helps speed up the whole process. In addition to that just the trial and error process I had to go through to see what works in a map and what works “even better” in a map has come a long way. When it comes to drawing mountains or certain symbols, I’ve had a lot more practice.

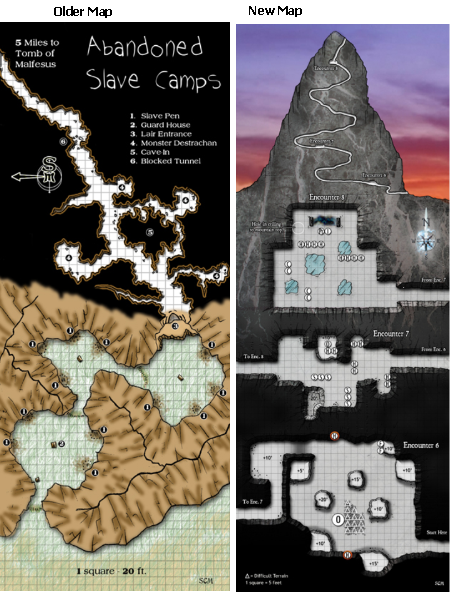

I can definitely see an evolution throughout the years in my work. Here’s an older map and a newer map to compare:

Jones: Any advice for all the amateur map-makers out there?

Macdonald: Well, if they are looking for advice on cartography in general I would suggest to just collect and review the work of those cartographers that inspire you. Study their work and see what it is about it that you like then try to create your own maps with your own unique style. Plus never give up. If you finish a map and are disappointed with how it turned out just work on making improvements on the next map. Even maps that are failures teach you something and in most cases you may tend to be too critical of your own work. Show them around and ask for advice. I remember when I started I got some good honest advice from some friends that I’m thankful for that made me change the way I was doing things and improved the overall quality of my work as a whole.

Jones: Lastly, what are you working these days:

Macdonald: Well, presently I’m working on some maps for a Catalyst Game Labs Shadowrun adventure. I’m also in the review stage for a couple maps for the Open Design Halls of the Mountain King. One of the dwarven maps was an isometric view of the underground royal residences that I think turned out pretty neat. Plus I just finished up some maps for Wizards of the Coast, and a project for the Green Ronin Freeport setting. So lots of interesting maps for a variety of settings.

Thanks to Sean for speaking with us! We look forward to featuring his work in future KQ and Open Design projects.

Great interview. Any chance of having those images link to full scale maps? That would be great.

The maps are very good looking!

The images are crushing on bandwidth already, and the WotC ones cannot be provided at full resolution.

Using them in a discussion of mapping at low resolution is covered under fair use. Using them at full res is potentially infringement.

The Open Design map, however, could be linked to higher-res. Hm.

Along with being an excellent cartographer, Sean runs one of the most fun D&D campaigns I’ve ever played in; he really puts my Kobold wizard through the paces. I urge everyone to buy lots of stuff with his maps so he’ll stay in a good mood and not do bad, bad things to poor little Smeepax.

Sean certainly has come a long way since working with us over at the Dragonlance Nexus. He’s one of our greatest success stories. He’s quite a talent, and just a great guy.

Trampas

Sean is one of the greatest people to work with. When I was writing Price of Courage, a huge Dragonlance adventure for Margaret Weis Productions, Sean and I would bounce ideas back and forth all the time for locations and encounter areas. Sometimes I would throw some crazy idea at him and he’d come back with this amazing map, which I would then turn into a series of cool encounters. I really hope I get to work with Sean again; I miss it!

Great article! As a member of the cartographersguild, I greatly enjoy seeing great maps and any tips anyone can provide is much welcomed.

I would love to know which programs he uses to work on those maps with. I keep thinking its something a bit easier to work with than Photoshop.

Crushing on bandwidth for those little jpegs? Maybe you need a better webhost…

Having just thumbed through my copy of _ToME_, I can concur with Mrs. Nephew’s comments– and given that there aren’t usually a lot of maps in Ars Magica stuff, it’s fantastic to have gotten such quality work.

-Ben.

Perhaps crushing is an overstatement. Let’s just say that the traffic and the file size together made a noticeable spike.

More visitors is certainly all to the good!

Great interview!

I also would be interested in knowing what programs he uses.

Great maps, and a fascinating interview… like Bog97th, I would also be interested in knowing what software Sean uses, in particular for the map of Armand’s Apartments.

Very nice interview and lovely maps!