While the column Real Steel offers insights into the forging of weapons, Alex Putnams’s Historical Steel column details their origins and use throughout history.

While the column Real Steel offers insights into the forging of weapons, Alex Putnams’s Historical Steel column details their origins and use throughout history.

___

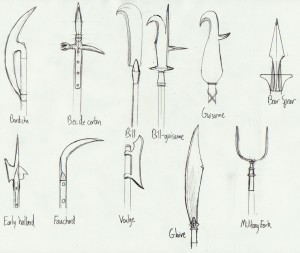

Swords get all the credit. Ever since the discovery of bronze, they’ve captured the imagination, appearing as heroic and knightly weapons—even on flags. Most legendary and mythological weapons are, of course, swords: you don’t hear about the variety of magical bec de corbins. But while a versatile weapon for close-in fighting, the sword had a few notable drawbacks:

- It was expensive: Well up until the 19th century and the Bessemer process, steel was expensive. A commoner or man-at-arms could own a sword, but it was a hefty investment, roughly equivalent to buying a new car.

- It was specialized: Different types of swords were optimized for fighting different opponents, and against plate armor, a cutting weapon isn’t very effective. Additionally, all types of sword fencing took considerable training

- It was a close combat weapon: Against a single opponent, a sword is a handy weapon. In a large battle, being close to an opponent is generally a liability, doubly so if one’s opponent is mounted…

And thus, the polearm (also called “pole weapon” or “staff weapon”) found its place as the primary weapon of the Medieval and Renaissance infantries. The simplest polearms were simply adapted peasant—or farming—implements with iron heads while the most complex were enormous, largely ceremonial affairs. Compared to swords, they were cheaper, easier to learn, and more effective. They gave the average soldier the advantage of reach and striking power—a long haft delivers more torque and angular momentum on the business end.

The confusing thing is that specific polearms rarely share unified, codified names. One man’s voulge is another’s halberd; a ranseur and a corseque might be the same thing; and “–guisarme” can be appended onto just about anything.

From a game standpoint, polearms can be as complex—or as simple—as your group desires, and at your gaming group’s discretion, similar polearms might be considered the same weapon in terms of rules. That way, characters who take the Weapon Focus (glaive) feat aren’t nearly so limited in what they can apply it to.

On the other hand, you could diversify polearms: since most gaming settings adopt arms and armor from a large swath of history, polearms could be diversified by culture: a cosmopolitan city might prefer gold-gilt partisans while a pastoral nation might be content with simple billhooks (which might be simple weapons for them rather thapn martial). That said, here’s an overview of the more notable types:

Ahlspiess/Awl Pike: A variant spear, the ahlspiess was a square-profiled spike, separated from a relatively-short haft by a rondel-style handguard. The ahlspiess was most common in Central Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Ahlspiess/Awl Pike: A variant spear, the ahlspiess was a square-profiled spike, separated from a relatively-short haft by a rondel-style handguard. The ahlspiess was most common in Central Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Bardiche/Berdiche/Berdysh: A hafted poleaxe most popular in Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and Russia from the 14th–17th centuries, the bardiche did not have much reach, as the haft was rarely longer than 5 ft. The blade was socketed to the haft at the center and sometimes the lower tip. The bardiche was prominently used by the Russian streltsy arquebusiers, who used the weapon as a shooting rest.

Lochaber Axe: A Scottish polearm, the Lochaber axe variously resembled a bardiche, voulge, or even a halberd, dependent on its construction.

Bec de Corbin/Lucerne Hammer: Two similar Renaissance polearms that are essentially pronged pole hammers, both featured a central spike. The primary edge of the bec de corbin (or “crow’s beak”) was a hooked spike while the Lucerne hammer (a modern name referring to the fact that quite a few of them were found in Lucerne, Switzerland) relied more on its pronged hammer head. Like the poleaxe, both were 14th–17th century weapons optimized against armor.

Bill/Billhook: The bill is essentially a curved agricultural pruning knife mounted on a pole. Originally an Anglo-Saxon weapon, it later combined the curved blade with a spear point, and it remained one of the two quintessential English weapons (along with the longbow), well into the 16th century. It was in use in Northern Ireland as late as 1798.

Boar Spear: A variant of spear used since Roman times, the boar spear features a crossbar, or lugs, behind the blade to prevent the blade over-penetrating (and allowing an angry boar to gore the hunter). Boar spears were used as weapons of war up to the Renaissance, and they remain in use today in their traditional hunting use.

Spontoon/Espontoon/Half-Pike: A ceremonial weapon used as a badge of rank in the 18th and 19th centuries, a spontoon was a short—approximately 6 ft. long—broad spear with a crossguard used much like a boar spear. Lewis and Clark’s Corp of Discovery used them to fend off grizzly bears.

Brandistock/Brandestoc/Feather Staff: A concealed self-defense weapon from Italy first popular in the 16th century, a brandistock was a walking stick with a blade or blades that could be shaken out (something like a gravity knife) to form a shortspear or trident. The Kariv switchpike from Kobold Quarterly #4 is a fantasy example.

Fauchard/Fouchard: A Medieval (11th–14th century) peasant’s weapon that is essentially a sickle mounted on a pole, and sharpened on the inner edge. Later usages of the word “fauchard” refer to a variety of glaive.

Glaive/Sovnya: A central-European polearm first popular about the 12th century, the glaive is essentially a single-edged sword or knife blade socketed onto a haft. Later glaives became increasingly ornamental.

Guisarme/Gisarme/Giserne: A somewhat nebulous polearm, the Medieval (11th–15th century) guisarme was basically a pruning hook, combined with a spear point. Later designs included a flute, a pronged hook on the backside of the blade for pulling riders off a horse.

—Guisarme: An ill-explained and often modern categorization, when added to the name of another polearm, “–guisarme” indicates a flute or prong on its back edge. For example, a glaive-guisarme is a glaive with a hook on the false edge.

Halberd/Halbard/Halberd: Originally a Swiss polearm from the 13th century, the halberd started as a voulge-like weapon combined with a spike. Later halberds became the familiar axe and pick mounted on a spear (rarely longer than 6 ft.). The halberd survives as a ceremonial weapon of the Vatican’s Swiss Guard.

Lance: The most familiar lance is the tapered tilting or jousting lance—purposefully designed to break—although the spear-like heavy lance and demi-lance (or light lance) were meant for mounted combat. Phased out in the early 16th century, light lances were reintroduced in 1816 by the British and survived until the 1920’s. Curiously, the word itself originally referred to a throwing spear, which gave English the verb “launch.”

Linstock: A polearm from the gunpowder age, linstock comes from the Dutch lontstok (or match stick) and describes a shortspear (3–4 ft. long) with clamps to hold an arquebusier’s or cannoneer’s slow match or fuse. In a pinch, it still worked as a weapon.

Military Fork: A weaponized pitchfork popular in France, Germany, and Italy from the 15th–19th centuries, the military fork consisted of just two tines on a pole, and could be used to lift supplies or siege ladders in addition to its obvious uses.

Partisan: Originally a 14th century spear with axe-like side blades, the partisan evolved to a spear-like weapon (sometimes slashing) with ornamental side prongs. It survives to the modern day in its ceremonial form.

Pike: An infantry longspear 10–22 ft. long, the pike revived phalanx tactics in the 14th century, whether on its own or to protect arquebusiers and musketeers as they reloaded. The bayonet slowly replaced the pike in the 18th century although shorter versions remained in use for another century.

Poleaxe/Pollaxe/Hache: An anti-armor weapon from the 14th century, the poleaxe was a short polearm with an axe head designed to crush plate armor, usually blended with a spike and a hook. Those with a hook were sometimes called bec de faucon (or “falcon’s beak”).

Quarterstaff: A stout pole about 6–8 ft. long (with the etymology for “quarter” up for debate), the staff could be made from a walking stick, a tool handle, or even a tree branch, though those meant for war where sometimes capped or shod in iron. The medieval staff was not held at the middle, but towards one end, rather like a spear.

Ranseur/Runkah/Rawcon: Popular in Central Europe from the 15th–17th centuries, the ranseur had a triangular spear blade flanked by two short parrying prongs.

Spetum: The predecessor to the ranseur, the spetum’s prongs were forward facing and more intended as blades in their own right than as parrying aids.

Corseque: The Corsican variant to the ranseur, the Corseque’s prongs feature exaggerated curves that may even bend backwards.

Voulge/Pole Cleaver: A primarily Medieval polearm similar to the glaive, the voulge typically features a less-curved, cleaver-like crushing blade, typically bound or riveted to the haft, while the glaive held a slashing blade that was usually attached via a socket.

War Scythe: Scythes meant for battle were not the S-curved farming implements, but weaponized variants that attached a scythe blade onto a straight pole to make a glaive-like weapon. War scythes were a peasant weapon, especially popular in Eastern Europe, and in occasional use up to the first part of the 20th century.

That was enjoyable to read and informative – thanks for this!

Great stuff; all these archaic polearm terms have been shrouded in mystery ever since EGG shotgunned a dozen ill-defined names at us in 1E. Love to see these guys subdivided by their general strengths: These ones are good for pulling guys off horses; these ones are good for penetrating plate mail, etc.

Polearms always seem to be underappreciated in RPGs. While the sword may be the weapon of the noble, spears, pikes and halberds tended to rule the battlefield. Inexpensive and effective, if not quite the great equalizer that the gun was, they allowed a group of peasant militia equipped with polearms to be a threat to a knight.

One of these days I’m putting a peasant mob into a game as enemies of some PCs. And I know what weapons they’ll be carrying.

Ahhh, I remember the olde days when villagers had torches and pitchforks. Along comes the likes of Wolfgang and we have common rabble with purpose made polearms – Villagers 2.0

Alex, this is good stuff. I’m looking forward to more!

Those aren’t pitchfolks, those are military forks, just by removing a tine! Alex says so… :)

Well, to be irritatingly specific, a pitchfork would have multiple (typically curved) tines and a short handle…and most early pitchforks weren’t even necessarily iron. A military fork was closer to a trident, less barbs, with U-shaped straight tines. And some military forks were hybridized with halberd/poleaxe-like side projections.

So yes, a military fork and a pitchfork are both forks. In much the same way that a dagger and a kitchen knife are technically both knives. ~_^

Wow! That was one thorough, comprehensive, and all-inclusive article about polearms. Well Done!

@ Alex Putnam: Regarding mediaeval pitchforks…

The Medieval Times dinner theater in Orland Florida used to have a Medieval Village “Living History” exhibit attached to it. The village was fantastic – worth far more than the price of admission! Amongst the many mediaeval crafts they demonstrated was how to grow a pitchfork:

Start with a young hardwood sapling. Prune away all but four branches, and “train” them (that is, forcibly shape the branches by using cords to bind and twist them) into the shape of tines. Let the sapling grow into this shape for another couple of years so that the branches thicken and harden, then chop it down and trim it up!