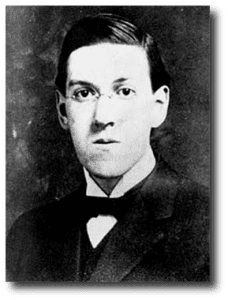

I just returned from the annual H. P. Lovecraft film festival in Portland, one of my favorite events of the year. As always, that event got me thinking (more than usual) about how the “Cthulhu mythos” can be incorporated into a fantasy RPG campaign.

I just returned from the annual H. P. Lovecraft film festival in Portland, one of my favorite events of the year. As always, that event got me thinking (more than usual) about how the “Cthulhu mythos” can be incorporated into a fantasy RPG campaign.

The elder gods run into trouble when they collide with heroic fantasy. Mighty warriors and wizards battle supernatural horror all day, every day. What makes Tsathoqqua and Shub-Niggurath any more frightening than a lich or a dragon?

Heroic FRPG adventures tend to be framed in terms of good versus evil. Villains strive to bring about some earthly manifestation of evil—greed, violence, hate, destruction. In Lovecraft’s brand of horror, evil and good are largely irrelevant. Boiled down to essential salts, this type of tale relies on four tenets.

The cosmos is huge, and humanity is small. Humans and demihumans are big fish only in their laughably small pond. On the grand scale of existence, our spot is near the bottom. There are creatures so far beyond us and our gods in age, understanding, and power that the ant/human analogy fails. We at least notice ants and find them interesting. The gulf separating us from the top of the scale leaves us more akin to dust than to ants.

Gods are not what we think they are. The beings that mortals revere as deities in typical fantasy worlds are nothing of the sort. They are above us on the power scale, but they’re just more of the same in the grand order (or disorder) of the cosmos. No entity of any real consequence watches over or protects us; we are alone and defenseless against an uncaring universe.

Reality is beyond our comprehension. Reality extends far beyond what we perceive; our limited senses barely scrape its surface. Far from being a curse, this is a blessing in disguise, because the human mind is too small, weak, and primitive to safely embrace anything beyond the sliver of existence that it sees.

And yet . . . There are creatures with knowledge and perception superior to ours with whom we can interact. Under the right conditions, they can even teach us things, but what we learn probably won’t be to our benefit. It’s more likely that they see us only as obstacles, rivals, or tools.

How can those principles be worked into a fantasy setting where the monstrous and the supernatural are encountered on a regular basis?

Some of the monsters that adventurers clash with undoubtedly are among those creatures that have a fuller grasp of the universe’s true horror than we have. Mind flayers, beholders, liches, sorcerers, the drow, even dragons might have pushed their consciousness into realms that are better left alone. This should seldom play to their or anyone else’s ultimate benefit. There’s a reason why it’s called forbidden knowledge.

Even in a heroic campaign, cosmic horrors need to remain beyond mortal comprehension and beyond mortal power to defeat. Anything else removes them from the realm of cosmic horror. Characters armed with fireballs and vorpal swords should never triumph dramatically over creatures that supersede the laws of human magic.

Instead, heroes must claim their victories by defeating the earthly minions and servants of such creatures and thereby forestalling their plans, temporarily. Characters can kill a dragon or destroy a whole city of beholders, but they should never get the idea that they’ve beaten an elder being from beyond the spheres of thought. It’s always out there, waiting and hungry, unknowable and unkillable. Does it want revenge? Probably, but not in terms that we would understand.

Its servants, however, are an entirely different story.

Next week, I’ll consider ways to punish heroes for crossing swords with the unknowable other than scooping out their minds or popping them like bubble wrap.

About the Author

Steve Winter has been involved in publishing Dungeons & Dragons in one capacity or another since 1981. Currently he’s a freelance writer and designer in the gaming field. You can visit Steve and read more of his thoughts on roleplaying games, D&D, and more at his website: Howling Tower. If you missed the first of these entries on the Kobold Quarterly site, please follow the Howling Tower tag to read more!

I don’t know if you watch anime at all but here’s one loaded with Cthulhu references, but not so much horror (except for the main character). Also the cutest Shantak Bird ever! http://www.animeseason.com/haiyore-nyaruko-san/

I have always loved the eldritch horror stuff but it is hard to achieve good horror in fantasy rpg, especially in most current games where encounters are balanced and players proceed from the notion that they will not encounter something they can’t handle. I am looking forward to some more good ideas next week.

One thing that helped make Lovecraftian creatures horrifying to my players is that (in my game, at least) they like to snack on sanity. Its not worthwhile to resurrect a character if the character is going to come back as a raving lunatic NPC. That uncertainty about recovering from death seems to make players extra-alert.

“Another sanity pretzel, Cthulhu?”

“Yes, thank you Shub-Niggurat. Ooh, this one is Lawful Good; they’re particularly crunchy.”

It’s important to note that Conan, one of the ur-tales of fantasy, takes place in a world that presupposes a Lovecraftian backstory.

If you really want inspiration on how to incorporate the Mythos, look to REH—he was a close friend of HP’s and they both kept in contact over the mythos.

I’m currently running a campaign filled with young adult players new to roleplaying gaming. They also have virtually no background in fantasy or sci-fi literature, save for one person, though they’ve all watched their share of modern horror films. I’m throwing in lots of Lovecraftian references and encounters as their games progress and they’re becoming more and more paranoid about the omens they’ve uncovered. Great fun!

Being a fan of mythos myself, I don’t think I agree with the assertion that heroes can never challenge the cosmic horrors, at least in the material reality. Cthulhu was put back to slumber by a mere ship being rammed into it. Epic level adventurers (I’ve been running D&D 4e for the last 3 years, I’ll use the slang) can do much more. Conan is a high paragon character in a low-magic setting, where most magic (unless I’m mistaken, as I haven’t read too much of his adventures) comes from deals with dark gods or cosmic horrors. That is not the core assumption of D&D. In D&D wizards stop time and clerics bring back the dead through their own power and the power of their (non-dark) deities. Just as importantly, problems are solved through combat. Once the characters get to the epic tier, they should be able to do *something* about the cosmic horrors, otherwise there was no point in them getting there.

In the campaign I’ve been running, the characters started by dealing with the machinations of the worshipers of the Patient One, a decidedly Cthulhu-esque Lord of Madness (as I’ve been referring to these things, after the eponymous 3.5 book) – in heroic tier. In paragon, they went around exploring the world, gaining support and gathering knowledge and artifacts they would need to deal with it. At the transition to epic, the Patient One almost broke free, and they had to deal with its influence over reality (http://magbonch.wordpress.com/2011/04/04/reality-breakdown/). Finally, in epic, they have used all the resources and support they’ve gathered to destroy the thing (http://magbonch.wordpress.com/2012/02/24/patient-one/ ; http://magbonch.wordpress.com/2012/02/28/patient-two/). This victory wasn’t achieved through stabbing it repeatedly, but the stabbing was a part of it.

They’ve only been able to do so because just as the Patient One’s mere presence was disrupting the material reality around it, the reality was constraining its power. In the Far Realm, where it and things like it come from, mortal magic is not going to do much. That’s where the true cosmicness of horror begins. At least in my game :)

The ‘false gods’ idea is probably the one that’s gone furthest into popular culture. Some people allege that ‘Chariots of the Gods’ is based on HP Lovecraft’s stories, for example. But it’s not necessarily bleak: John Carter (and I think Captain Kirk as well) overthrew some false gods, in the context of a very ‘upbeat’ adventure.

This is a very good summary Steve. You have stated in a few easy to read paragraphs the essence of this genre. Well done! This is worth sharing.