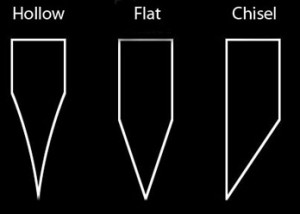

There are three basic edge geometries used on cutting tools, and those three types have some variations. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and some are useful only on specialized tools. Each type has its advocates, and some makers like one type so much that they specialize in making only that type of edge.

There are three basic edge geometries used on cutting tools, and those three types have some variations. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and some are useful only on specialized tools. Each type has its advocates, and some makers like one type so much that they specialize in making only that type of edge.

The Hollow Grind

The hollow grind, or concave grind, is probably the most familiar; you’ve probably at least heard of it, even if you don’t know what it is. It’s created on a wheel, either on a stone or a belt grinder’s contact wheel. Its primary advantages are extreme sharpness and the ability to approach a cut at a very acute angle and bite without sliding. Its biggest disadvantage is that it doesn’t have much steel behind the edge, so it’s fragile compared to other grinds. You have to be careful when initiating this grind to get it established at the same height on both sides of the blade. Once established, it’s the easiest grind to finish because the grinder wheel wants to stay in the hollow that’s created. This grind is often used on fine cutting instruments, such as razors and scalpels.

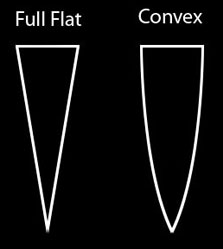

The Convex Grind

The convex grind, also called the Moran grind or apple seed grind, is the geometric opposite of the hollow grind. Instead of having a hollow, it has a “belly.” It’s most easily created on the slack belt area on a belt grinder. Its biggest advantage is that it has a lot of steel behind the edge, so it’s sturdy. Its biggest disadvantages are that it’s difficult to make it extremely sharp (but it’s not impossible), and it’s the edge most difficult to initiate a cut at an acute angle without slipping. This grind is often used on hacking and chopping tools, such as axes, swords, and big knives. This is my favorite grind, and when it’s done properly, in my opinion, it’s the most versatile. Contrary to popular belief, this grind is capable of extreme sharpness, and I think it’s the best grind for kitchen knives because the “belly” pushes the item being cut away from the blade, rather than letting it stick. I do this grind so it’s almost flat. It took awhile to get it right, but I swear by it now.

The convex grind, also called the Moran grind or apple seed grind, is the geometric opposite of the hollow grind. Instead of having a hollow, it has a “belly.” It’s most easily created on the slack belt area on a belt grinder. Its biggest advantage is that it has a lot of steel behind the edge, so it’s sturdy. Its biggest disadvantages are that it’s difficult to make it extremely sharp (but it’s not impossible), and it’s the edge most difficult to initiate a cut at an acute angle without slipping. This grind is often used on hacking and chopping tools, such as axes, swords, and big knives. This is my favorite grind, and when it’s done properly, in my opinion, it’s the most versatile. Contrary to popular belief, this grind is capable of extreme sharpness, and I think it’s the best grind for kitchen knives because the “belly” pushes the item being cut away from the blade, rather than letting it stick. I do this grind so it’s almost flat. It took awhile to get it right, but I swear by it now.

The Flat Grind

The flat grind is generally considered to be a compromise between the other two types. It is easiest to make this grind on the flat platen (it’s a flat metal, glass, or ceramic plate behind the belt that provides a hard flat surface to push against when grinding) of a belt grinder. Because it’s a compromise, you can find this grind on almost any cutting instrument, but it is most often found on medium to large knives, such as camp knives and Bowies.

The Chisel Grind

The chisel grind is simply a “half grind”; only one side of the blade is ground. It can be done in hollow, flat, or convex (a flat is shown), but the most common configuration is a hollow chisel. It is the most fragile type of edge, but the sharpest. Straight razors are often a hollow chisel grind. Chisel grinds are either left or right handed, which seriously limits its functionality. The name derives from chisels, which are ground this way to prevent the tool from plunging, as well as making them very sharp.

So Now You Know

I hope I didn’t bore you too badly, but this is a pretty important topic if you want to understand edged tool construction.

Between weather and time I haven’t been able to do another video, but we’ll get to it soon.

Any questions?

Correct me if I’m wrong, but aren’t katanas chisel ground? I just want to make sure I’m right about this.

Convex grinds are easy to maintain, but can be hard to achieve. A fair-sized scrap of leather and some polishing compound is all you need to sharpen it.

Andrew – IIRC, Katanas are flat edged, but the blade was convex. Tantos (at least the popularized ones) are chisel ground, and they’re a pain in the butt to use delicately; they tend to curve as you cut.

@AndrewFoose – Kurt is correct, traditional katanas are convex (on both sides, so not chisel). You need a convex blade if it’s going against armor – which the katana did.

@Kurt Schneider – I use my belt grinder to sharpen convex blades, so I don’t have to come up with neat ideas like using leather and compound – what a great idea! The leather gives enough to accommodate the blade shape.

You’re correct about many (not all) “popularized” tanto being chisel ground – traditional ones, especially bigger ones, were also chisel ground. The even smaller kozuka was almost always a chisel grind.

Interesting as always

@Darkjoy – good to hear it. I was afraid this would be a tad dry.

Nice article! Who cares if it’s a bit dry, I’m sure folks learned something.

Always looking forward to new articles (and I’m especially looking forward to my newest knife).

@Adam Daigle – I just sent you an email – expect it Saturday! :)

Kitchen-folk and blade-folk always get along and see eye to eye. I’m glad we met through gaming. Can’t wait to use the knife. :)

You did not bore us, not in the least – I’m surprised you’d even think that. Based on what I see in the forums, KQ attracts a pretty intelligent and imaginative crowd. The sort of folks who are eternally hungry for good solid facts. Please, keep feeding us! :)

@Adam Daigle – Yeah, pretty twisted karma that puts us all together, isn’t it?

@Charles – I agree, this is a bright group. I was just concerned that the circle of interest mightn’t extend this deep into the subject. I’m happy it does…

More snacks on the way!

I’m still interested in the article on steel types that I commented about a few “Reel Steels” back.

@Jeff Dougan – I’m glad you threw that out there again. It’s unlikely I’ll do another outdoor video till March or April, so I don’t see why not do steel types next.

Then maybe a spear? (don’t recall one being done before, so I figure I can ask)

Can’t edit my comment, but caught that I did, in fact, miss a spear. Catch-up reading to do later tonight, I see.

Arrowheads? or are they too simple/complex?

Bodkin arrowheads have been requested and on the list – I’ll probably cover other types at the same time. Maybe more on spears also…